Tools and methods for recording interviews with enough audio fidelity, integrity and selectivity to support social research may seem relatively mundane or matter-of-fact. And for some research purposes, almost any digital or tape-based audio recorder will suffice. But choices among different methods and technologies can also shape important theoretical priorities and concerns. That’s also true for choices about how a recorded interview will be processed, converted, examined, analyzed or reproduced.

Traditionally, the first step in the post-interview workflow was to make a written transcript of the audio recording, a verbatim text that could then be edited or analyzed. That’s still a very common practice, but recent software and hardware developments make possible some intriguing alternatives. Choices between these alternative “methods” involve matters of personal preference and technical skill, but they also reflect and support different kinds of theorizing about the substance of culture and social life in general and the “content” of interviews in particular.

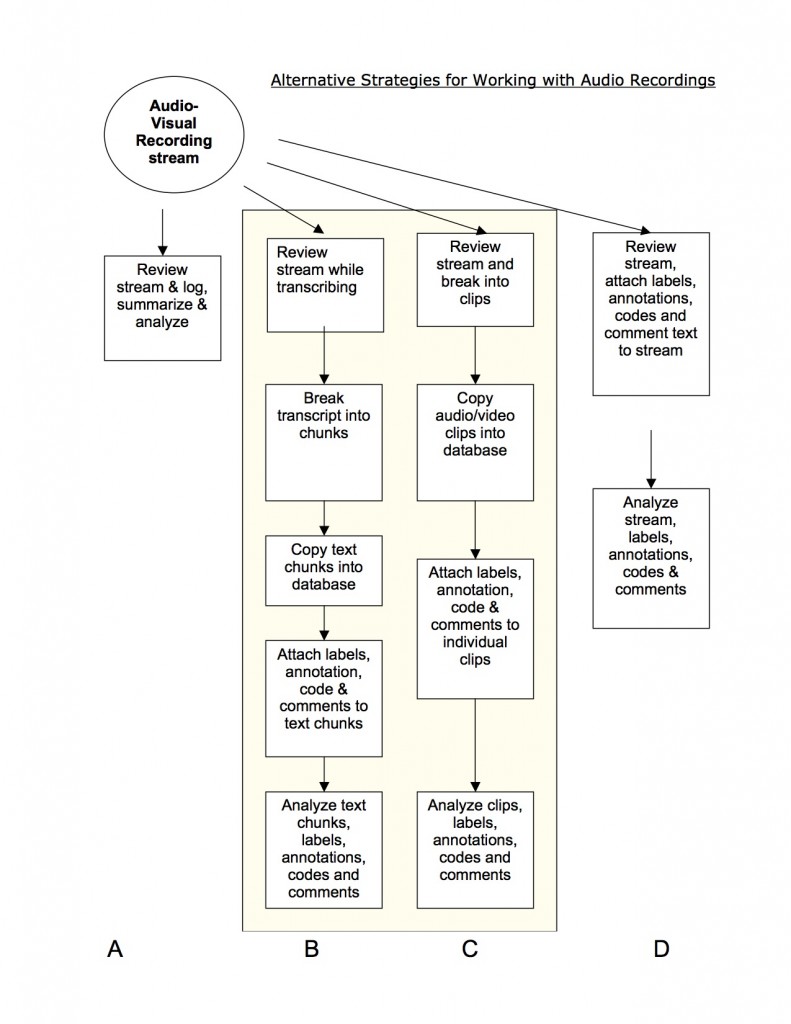

Some of these choices are displayed in the figure above as four different strategies for working with an audio recording of an interview. Each strategy appears as a vertical column (labeled at the bottom as A, B, C and D) that starts with the same audio recording “stream.” In column ‘A,’ the strategy involves listening to the recording and making more or less detailed notes with a standard word processing program. The product of this method could be a log of the interview (in which a few details or themes are indexed to sequence or duration), a narrative or thematic summary of the interview, or a verbatim transcript (that might also include some features of a log or summary). When the process is complete, the researcher has in hand a text that can stand in for the audio recording in any subsequent rounds of analysis or reporting.

The second and third columns (‘B’ and ‘C’) suggest two different ways of building computer data base functions into the analysis of the same audio recording. In the Column ‘B,’ a written transcript is prepared, much as it might be in column ‘A’, but the transcript is then broken into chunks that are imported as individual records in a data base program. Each chunk of text, or record, can be coded and annotated, retrieved, and re-assembled according to different themes. This “code and retrieve” approach enables a researcher to bring together related comments from the same or different interviews for further analysis. It entails the same kind of conversion from audio to text that takes place in strategy ‘A’, but the “text” product itself is enriched to include not only a sequential summary or transcript, but a database of text “chunks” drawn from it.

In strategy ‘C’ the same data base features appear that were part of strategy ‘B,’ but with an interesting twist. Rather than first converting the audio recording into a text, and then breaking up the text into meaningful chunks, the audio recording itself is broken into chunks, with each chunk then identified with particular themes, questions or issues. Once again each chunk appears as an individual data base record, but the records themselves include a section of the audio recording. In contrast to ‘B,’ strategy ‘C’ allows analysis of the interview to be based on the audio recording itself (not a text translation of the interview) and leaves open the option of selective transcription after analysis is concluded. That said, both ‘B’ and ‘C’ split the continuous coherent “stream” of the audio recording (or its text transcription) into discrete chunks, which may or may not make sense for a particular line of inquiry.

In the far right column I have suggested a fourth approach that combines features of the preceding three. Strategy ‘D’ starts with the same audio recording as ‘A,’ ‘B’ and ‘C,’ but preserves that recording intact through subsequent rounds of analysis or transcription. In contrast to the other three approaches, text transcriptions, codes and annotations are attached directly to the audio recording as another “layer” of a digital file. This transforms the audio stream into an audio-text database; text is segmented and indexed to different sections of the audio recording without fragmenting the recording. Working with strategy ‘D,’ a researcher could listen to the entire recording, locate audio segments by searching for code words or summaries assigned to them– within or across interviews. This strategy thus preserves all the information of the source audio recording throughout the process of analysis.

These four different approaches present somewhat different technical challenges, but they also support different kinds of interview-based studies and different kinds of theorizing about culture and social life. To understand the implications of these contrasts it’s useful to consider four related distinctions: data “chunks” and “streams;” analytical “annotation” and “coding;” “audio” and “text” representations;” and the boundaries between “informants,” “colleagues,” and “audiences.”